Properties of operations

Commutative property

A binary operation * on a set S is commutative if:

We say that “x commutes with y“, or that “x and y commute under *“.

Associative property

A binary operation * on a set S is associative if:

Distributive property

A binary operation * on a set S is distributive over a binary operation + on S if:

Fractions

Multiplying fractions

Dividing fractions

Dividing by a fraction is the same as multiplying by the reciprocal.

Removing common factors

Distributive law with fractions

Adding mixed-denominator fractions

When the denominators have a common factor, first separate these out to the side and then multiply by the uncommon factors. This saves time and effort with complex equations. In the following example, x and 3 are the uncommon factors.

Exponents

Basic forms

Fractional exponents

Negative exponents

Multiplying exponents

Dividing exponents

Exponents of exponents

Distributive law with exponents

Exponentation distributes over multiplication.

Notation for roots

- The expression \sqrt{x} or x^{\frac{1}{2}} represents the positive square root.

- The expression -\sqrt{x} or -(x^{\frac{1}{2}}) represents the negative square root.

- The expression \pm\sqrt{x} or \pm(x^{\frac{1}{2}}) represents both square roots.

- When asked to ‘solve for x when x^2 = 4, both roots are required.

Multiplying conjugate roots

The conjugate of \sqrt{x} + \sqrt{y} is \sqrt{x} - \sqrt{y}, and vice versa.

Rationalising the denominator

For any fraction with a square root in the denominator, we can lift the square root up to the numerator by multiplying both the numerator and the denominator by the conjugate of the denominator.

Equations and inequalities

To preserve an equality, any operation performed on one side of the equality must also be performed on the other side.

Notation for intervals

- x \in (a, b) denotes an open interval (where a < x < b)

- x \in [a, b] denotes a closed interval (where a <= x <= b)

- Intervals can also be half-open (as x \in (a, b] or vice versa)

Multiplying or dividing by a negative value

When multiplying or dividing an inequality by a negative number, we must reverse the direction of the inequality (the signs of both values flip and they end up on opposite sides of zero).

We can’t multiply or divide an inequality by an unknown term, because the sign of that term isn’t yet known. To deal with this, we use addition and subtraction to rewrite the inequality to have zero on one side, and then we solve to find the values of the unknown terms.

Critical points for inequalities

See critical points.

A critical point is the argument of a function where the function derivative is zero (a stationary point) or undefined.

A point at which a term changes sign is also called a critical value.

The critical value of an inequality is, say, for x < \frac{1}{2} the critical value will be \frac{1}{2}, because x = \frac{1}{2}.

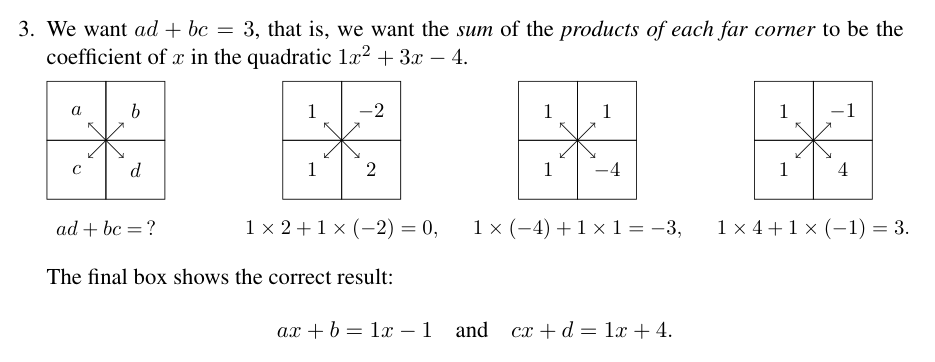

Solving quadratic equations by factoring

It is much easier to work with and to solve quadratic equations that are in a factored form. The factored form of a quadratic equation is the product of two linear forms:

There’s a visual aid with boxes that can help with finding these linear forms from the expanded polynomial form:

When we solve a quadratic equation, we are finding the values for each variable that will make the equation true. Every quadratic equation will have zero, one, or two real solutions.

We can use the fact that if ab = 0 then a = 0 or b = 0 (or both). Given a factored quadratic equation in the form (ax + b)(cx + d) = 0, we know that either ax + b = 0 or cx + d = 0.

In the example equation x^2 + 3x - 4 = (x+1)(x-4) from above, x = -1 or x = 4.

Solving quadratic equations by completing the square

If the result is the difference of two squares (so \frac{b^2}{4} - c \geq 0) then we can solve the equation. If, however, the result is the sum of two squares (so \frac{b^2}{4} - c < 0) then the equation has no real solutions.

Once the equation is in the form (x + \frac{b}{2})^2 - \frac{b^2}{4} + c = 0, we can see that (x + \frac{b}{2})^2 = \frac{b^2}{4} - c. To find the solutions of x, we take the square root of both sides and solve for x:

Solving quadratic equations using the quadratic formula

The coefficients of the polynomial can be substituted into the equation and then solved to directly find the values of x.

The discriminant is the portion b^2 - 4ac beneath the square root, and can be used to determine the number of real solutions. If the discriminant is negative, there are no real solutions to the equation. If it’s zero, there’s one, and if it’s positive, there are two.

Geometry

Equation of a line

A more useful form is y = mx + c, where m is the gradient of the line and c is the y-intercept.

The gradient m of a straight line can be found by choosing any two points (x_1, y_1) and (x_2, y_2) on the line and dividing the vertical displacement by the horizontal displacement:

The gradient m of a line is also given by \tan \theta, where \theta is the angle measured anti-clockwise to the point from the positive x-axis. The angle can be recovered from the gradient with \theta = \tan^{-1} m.

Equation of a line given a point and a gradient

To find the equation of the line passing through (1, 4) with gradient \frac{3}{2}, we substitute the values into the equation m = \frac{y_2 - y_1}{x_2 - x_1}:

Finally, cross-multiply and expand:

Equation of a line given two points

To find the equation of the line passing through two points, we first find the gradient of the line with the equation m = \frac{y_2 - y_1}{x_2 - x_1}, and then we use the previous method with a point and gradient.

Parallel and perpendicular lines

If two lines are parallel, they have the same gradient.

If two lines are perpendicular, the product of the gradients is -1 (that is, m_1 m_2 = -1). This means that m_1 = - \frac{1}{m_2}, so we can find a perpendicular gradient by negating the reciprocal of the original gradient.

Solving linear equations in two variables

For example, to find the value of x and y in the following linear equations:

We start by multiplying every term in one equation by a constant, in order to make the coefficients of one of the terms the same in both equations:

Finally, we can subtract one equation from the other and solve for y, and then substitute that value into one of the equations so that we can solve for x. If there is no valid solution (such as when subtracting one equation from the other would remove both variables), then the lines are parallel.

Equations of the basic graphs

| Equation | Graph name |

|---|---|

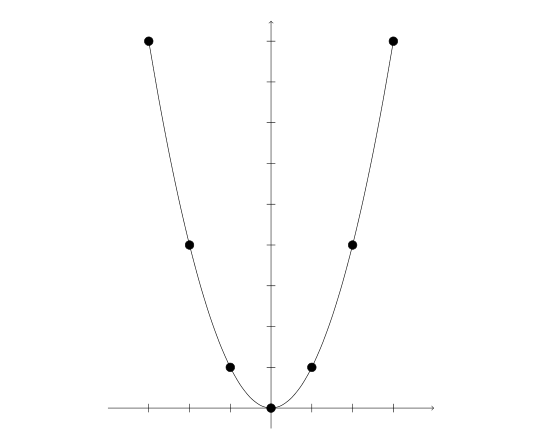

| y = x^2 | Parabola |

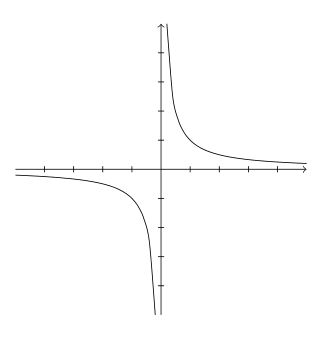

| xy = 1, y = \frac{1}{x} | Rectangular hyperbola |

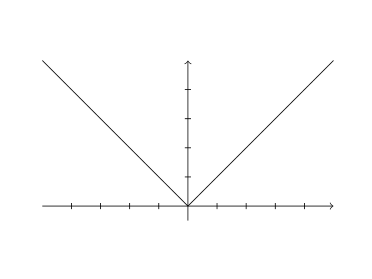

| y = |x| | Absolute value |

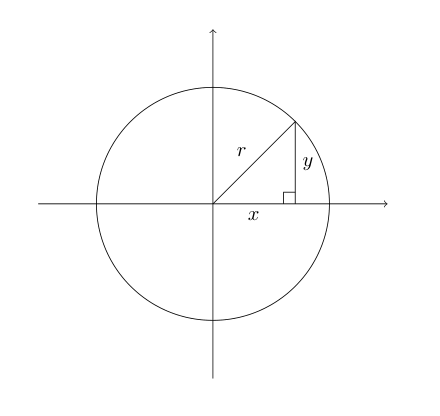

| x^2 + y^2 = r^2 | Circle |

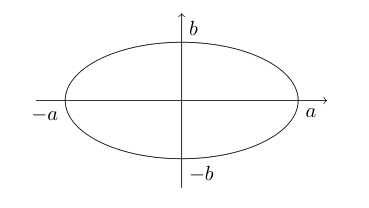

| \frac{x^2}{a^2} + \frac{y^2}{b^2} = 1 | Ellipse |

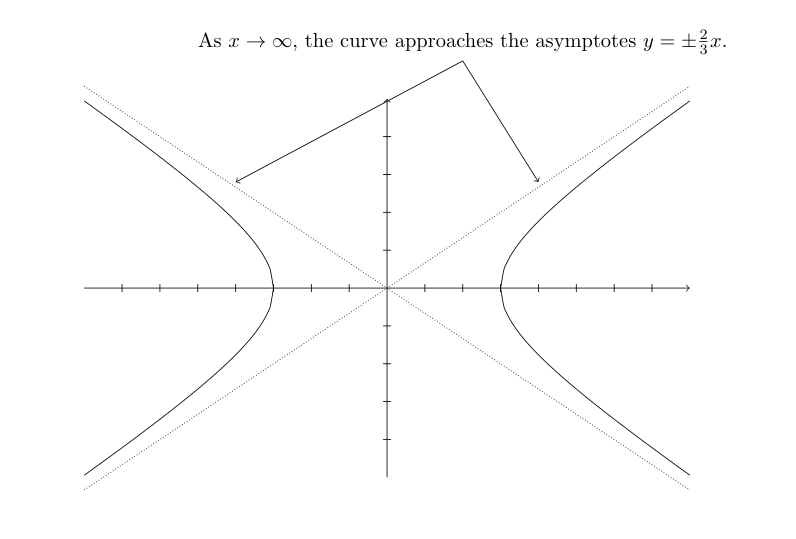

| \frac{x^2}{a^2} - \frac{y^2}{b^2} = 1 | Hyperbola |

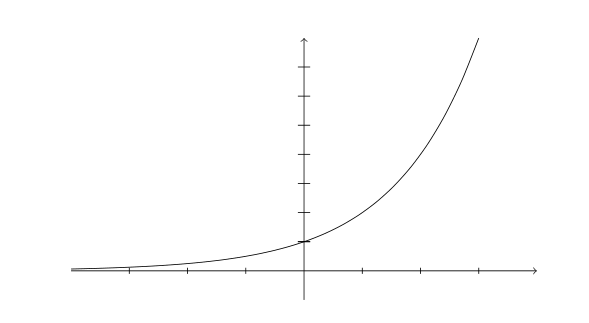

| y = a^x | Power function |

For the rectangular parabola:

- as x \to \pm \infty, y=0

- as x \to 0, y \to \pm \infty

For the ellipse:

- a and b are positive numbers

- -a \le x \le a

- -b \le y \le b

- if y=0, then x = \pm a

- if x=0, then y = \pm b

For the hyperbola:

- a and b are positive numbers

- y is undefined when -a < x < a

- if y=0, then x = \pm a

- as x \to \infty, y = \pm \frac{bx}{a}

Asymptotes

An asymptote is a line (not necessarily horizontal or vertical) which a curve approaches as x \to \infty or y \to \infty.

Functions

Function composition

Inverse functions

To calculate the inverse of a function f^{-1}, swap x and y and then make y the subject of the equation.

To check the inverse function, apply it to the original function. The result should be the identity function.

Differentiation

The equation for the derivative of a function is:

The derivative of a function is only defined where the function is defined and is continuous (not a break, gap, sharp point, or end).

Notation for differentiation

Leibniz notation for the first derivative is \frac{\dy}{\dx}, or \frac{\dd}{\dx}[y], or \frac{\d{f(x)}}{\dx}, or \frac{\dd}{\dx}[f(x)]. Notation for the second derivative is \frac{d^2y}{\d{x^2}}. \dy represents an infinitesimal change in y, whereas \Delta y would represent a real change in y.

Lagrange notation for the first derivative of f(x) is f'(x), and for the second derivative is f''(x).

Basic rules for differentiation

First, every term in the expression that does not contain a bound variable is removed. These terms are all constants and do not contribute to the gradient of the function.

For every term in the expression, we multiply the term by the power and then decrement the power by 1:

The derivative of the sum is the sum of the derivatives:

Chain rule

To find the derivative of a function g(x) to the power of n, multiply by the power and reduce the power by 1 as usual, but also multiply by the derivative g'(x) of the function. In other words, n \times g'(x) \times g(x)^{n-1}.

To find the derivative of a trigonometric function applied to a function g(x), multiply by the derivative g'(x) of the inner function, and replace the trigonometric function with its derivative.

To find the derivative of any composite function f(g(x)):

A second, equivalent formula is given as follows:

As an example, the equation h(x) = (3x+1)^{10} has h(u) = u^{10} and u(x) = 3x+1.

Product rule

To find the derivative of a product of two functions f(x) and g(x):

Quotient rule

Concavity

If the slope of a function is increasing (the second derivative of the function at that point is positive), the function at that point is concave up (looks like a cup), and a turning point is a relative minimum.

If the slope of a function is decreasing (the second derivative of the function at that point is negative), the function at that point is concave down (looks like an umbrella), and a turning point is a relative maximum.

Critical points

A critical point is a point where the derivative is zero or undefined.

To find the critical points of a function, first find the derivative of the function. Check for all values of x where the derivative is undefined, and then solve the derivative for zero. Finally, substitute the solved x values into the original equation to find the full coordinates of every critical point, if that point isn’t an asymptote.

Turning points

A turning point is a point where the slope of a function changes from negative to positive (or vice versa).

The first derivative of the function at a turning point is zero. If the slope changes from positive to negative (the second derivative at that point is negative), the point is a relative maximum. If the slope changes from negative to positive (the second derivative at that point is positive), the point is a relative minimum. Otherwise, the point is a point of inflection, not a minima or maxima.

Point of inflection

A point of inflection is a point where the concavity of the function changes. The first derivative at a point of inflection is not necessarily zero.

If the second derivative of a function at a point is zero (the second derivative changes sign at this point), the point is a point of inflection.

Second derivative test

To determine whether a point (where the first derivative is zero) is a minimum or a maximum, we can check the sign of the second derivative at that point:

- if the second derivative is negative, the slope is decreasing, and the point is a relative maximum

- if the second derivative is positive, the slope is increasing, and the point is a relative minimum

- if the second derivative changes sign (passes through zero), the point is a point of inflection

First derivative test

This test is for cases where the second derivative is tedious to find.

If the first derivative at a point is zero and:

- changes sign from positive to negative, the point is a relative maximum (concave down)

- changes sign from negative to positive, the point is a relative minimum (concave up)

- does not change sign, it is neither a minimum nor a maximum, but could be a point of inflection

To check how the sign changes, we calculate the value of points to the left and right.

Trigonometry

The convention noted in the MATHS 102 coursebook is that degrees are given to 1 decimal place, and radians to 4 significant figures.

Convert polar to rectangular coordinates

Where 0\degree \leq \theta \leq 90\degree:

When 90\degree \le \theta \leq 180\degree, we use 180\degree - \theta as the angle and negate the result:

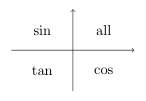

The angle used must always be the acute angle made with the x axis. The following diagram shows which ratio is positive in each quadrant:

Finding angle of point to x-axis

Draw the point and angle on a pair of axis, label the opposite and adjacent with lengths (which are always positive), use \tan^{-1}(\frac{y}{x}) to find this angle, and then offset the angle to the correct quadrant as needed.

Definition of tan

Convert between degrees and radians

To convert degrees to radians (equation looks like a d):

To convert radians to degrees (equation looks like an r):

We can also see this as converting the unit to turns and then converting from turns to the target unit. For radians to degrees, we divide by 2\pi (the number of radians in a turn), and then multiply by 360 (the number of degrees in a turn):

Calculate arc length

The arc length subtended by an angle of \theta radians in a circle of radius r is r \times \theta.

If the angle is given in degrees, first convert to radians.

Special triangles

The 1 : 1 : \sqrt{2} triangle has angles 45\degree and 45\degree (\frac{\pi}{4} and \frac{\pi}{4}).

The 1 : 2 : \sqrt{3} triangle has angles 30\degree and 60\degree (\frac{\pi}{6} and \frac{\pi}{3}).

Graphing the trigonometric functions

\sin has range [-1, 1], period 2\pi, and y-intercept 0.

\cos has range [-1, 1], period 2\pi, and y-intercept 1. It is the same as \sin shifted left by 90\degree.

\tan has period \pi, with y = 0 at each multiple of \pi and asymptotes midway between each multiple of \pi.

Inverse trigonometric functions

Power notation

When the power is -1, the notation is overloaded to instead mean the corresponding inverse trigonometric function.

Solving trigonometric equations

Take the following equation:

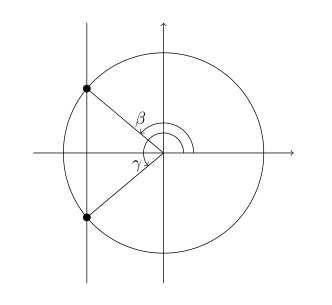

We start by drawing the line x = -0.4 over the unit circle. If the function were \sin, we’d draw y = -0.4. If the function were \tan, we’d draw y = 0.4x (from \frac{y}{x} = 0.4). Mark the two intersection points, and draw radii to them. We’re looking for the angles to each of those radii from the positive x-axis.

Next, calculate the closest angle to either radii from the x-axis with \arccos(0.4). We drop the sign here, because the inverse functions only act in the first quadrant. This yields 1.159 (to 4 significant figures). If the ratio can be found on one of the special triangles, it’s best to use it to find the angle in terms of \pi.

Finally, we offset the angle into the correct quadrants and find x to be \pi - 1.159, \pi + 1.159. The MATHS 102 coursebook rounds the angles immediately, not waiting until the end.

Addition identities

How to derive these identities

When solving a \tan equation, if either x or y is not defined, use the following instead:

When deriving the \tan equation from \tan\theta = \frac{\sin\theta}{\cos\theta}, expand the \sin and \cos as above, and then split the terms and divide every term in the fraction by \cos\theta\cos\phi. Finally, cancel factors and simplify.

Double-angle identities

Derived from f(\theta + \theta):

Further, because 1 = \cos^2 \theta + \sin^2 \theta, we have:

Half-angle identities

Derived from f(\frac{\theta}{2}+\frac{\theta}{2}):

Power reduction identities

Replace a product with a sum

Derived from the addition formulae above, f(\theta + \phi) \pm f(\theta - \phi). Work backwards from \sin(\theta + \phi) + \sin(\theta - \phi) = 2\sin\theta\cos\theta.

Replace a sum with a product

If x = \theta + \phi and y = \theta - \phi, then x + y = 2\theta and x - y = 2\phi. We can substitute these into f(\theta) \pm f(\phi), starting from \sin\frac{2\theta}{2} + \sin\frac{2\phi}{2}.

Another approach is to rewrite f(x) \pm f(y) as f(\theta + \phi) \pm f(\theta - \phi) and expand and simplify from there.

Reciprocal functions

Using 1 = \sin^2\theta + \cos^2\theta, we can see that:

By dividing instead by \sin^2\theta, we get:

Derivatives of trigonometric functions

Logarithms

If f(x) = 2^x, then f^{-1}(x) = \log_2 x. This is the function reflected by the line y = x.

\log_n x is not defined for x \le 0. It intercepts the x-axis at x = 1.

Composing exponentation function with logarithm function

If f(x) = a^x, then f^{-1}(x) = \log_a x. Since f(x) \circ f'(x) = f(f'(x)) = x:

Addition and subtraction of logarithms

Beware of the following common error:

Multiples of logarithms

Taking both sides of an equation

Exponential function

Has a y-intercept of 1, and is always positive, with a positive slope. As x \to -\infty, e^x \to 0, and as x \to \infty, e^x \to \infty

e^{-x} is a reflection of e^x in the y-axis.

Natural logarithm function

Undefined at x = 0.

Summation

A list of numbers given by a function on the set of integers \bb{Z} is called a sequence.

The sum of a sequence is called a series.

Factoring a sum

We can factor out a constant multiple from all the summands. That is, multiplication is distributive over addition.

Summation of sums

The sum of two summations is the summation of the sums. That is, addition is associative.

Consecutive sums

Consecutive sums can be combined.

Summation of constants

Useful formulae

The formula for the summation of consecutive natural numbers:

The formula for the summation of consecutive squares:

Arithmetic sequence

An arithmetic sequence starts at a constant a, with each term being equal to the previous term plus a constant d.

The sum of an arithmetic sequence is:

Geometric sequence

A geometric sequence starts at a constant a, with each term being equal to the previous term multiplied by a constant r.

The sum of a geometric sequence is:

If |r| < 1, then the sum of an infinite geometric sequence is a finite number, and is:

Integration

\int 3x^2 dx means to find the function whose derivative with respect to x is 3x^2.

Basic rules for integration

Constant factors can be pulled out of the integral:

The sum of integrals is equal to the integral of a sum:

The integral of a constant a with regards to \dx is ax + c:

Integrating polynomials

Terms are integrated separately, much like how terms are differentiated separately during differentiation.

Integration by substitution

This is analogous to the chain rule for differentiation.

Substitute a function f(x) with u, replace dx with du such that the equation is equal to the original, then integrate, and finally replace u with f(x).

For example, to integrate the following equation:

Start by integrating both terms separately, pulling out any constant factors:

We can’t integrate the product in the second integration directly. Instead, we temporarily substitute the inner expression x^2 - 2x + 7, calling it u, and we now integrate the second integration with respect to du:

This isn’t quite right though, because we don’t know that \d{u} is equal to \dx. We also want to be removing the (x-1) factor at the same time. Find out what du is by differentiating our expression u and then manipulating the equation until \d{u} = (x-1)\dx:

Now we can see that the (x-1)\dx in our second integration can be replaced with \frac{1}{2}\d{u} (pulling the \frac{1}{2} constant factor out of the integration for tidiness):

Now integrate, remembering to add c (since c is a random constant, any multiple of c is equal to c):

Substitute u for our original expression x^2 - 2x + 7, and then simplify to get the final answer: