This weekly debrief is for paying supporters of my work. Please only read if you’ve paid. Thanks!

→ Click here if you've paid ←

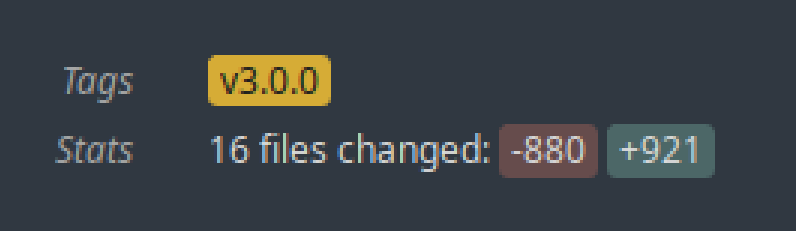

This week has been spent working on a new major version of the Torque meta-assembler, which involved a significant rewrite of the internals.

Torque

I prefer to take a steady and methodical approach to programming, working on one feature at a time and ensuring that every commit is tidy, documented, and buildable. There are some tasks, however, that resist this gentle approach and necessitate the application of brute-force and an iron stomach. These are the days with line counts numbering in the hundreds or thousands, where type errors clot on the floorboards and the electric tang of ozone hangs in the air. This rewrite was one such task.

A bit of history

I first released Torque in April of this year to a surprisingly enthusiastic response. I’d initially designed and written the assembler out of necessity, wanting to write programs for a PIC microcontroller but being stymied at every turn by the official MPLAB IDE (a lumbering and terrible beast of a program). I had the datasheet for the microcontroller right in front of me, all I needed was a way to lever the right bits into the right order to match the listed instruction encodings.

After I released Torque there came a flurry of activity, with a lot of ideas of how to make Torque more flexible and general. Torque gained first-class strings, negative integers, limited recursion for macros, and a few more expression operators, but I was limited in how much I could change without breaking apart the foundations.

Gödel’s curse

The most important change that I wanted to make in Torque was to allow label addresses to be used in the predicate for a conditional block. This was expressly forbidden in version 2 because of the way that label addresses were calculated.

In that version of Torque, conditional blocks were assembled first and then label addresses were calculated and back-filled into the program. This was to prevent an issue where if a label address changed the predicate of a conditional block, and if the label definition came later in the program, the conditional block could shift the label definition to a new address, which could affect the predicate and change the label address a second time. The following short program is an example of one such ‘undecidable’ program: if the end label address is even, the macro will insert a zero byte, making the address odd, causing no byte to be inserted, looping ad infinitum.

( Insert a zero byte only if n is even. ) %PAD-IF-EVEN:n ?[n 2 <mod> 0 =] #00000000 ; ( Padding will increase the label address by 1, making it odd. ) PAD-IF-EVEN:end @end

This program (and any other program in which a predicate contained a label reference) cannot be assembled in version 2 of Torque. But there are a lot of valid programs that rely on generating different code for different address values. An align macro could be used to insert bytes until the address is a multiple of n, and a jump macro could automatically choose between a relative jump or an absolute jump based on distance to the jump target. I needed to find a way for Torque to correctly reason about these types of programs.

The solution

Version 3 of Torque solves this issue by calculating label addresses while the program is being assembled, instead of calculating them afterwards and back-filling the address values. The address of each label is assumed to be zero until the matching definition has been reached and the real value calculated, which means that any forward references will use the wrong address value. Torque keeps track of the initial and calculated addresses for each label, so that it can determine whether the program assembled correctly.

If the calculated final address of a label is not equal to the initial assumed address, the program will be assembled a second time, using the addresses calculated during the previous round as the initial addresses. After this second round has completed, the initial and newly calculated address values are compared, and if they still haven’t stabilised then the program is assembled a third time, with the hope that the addresses will eventually line up. If a program still hasn’t stabilised after a set number of rounds, an error is printed that indicates the location of the label at fault.

An example in Uxn

The following Torque program demonstrates how we can take advantage of the changes in Torque to create an optimising jump macro when writing programs for Uxn, a portable virtual computer system that inspired Bedrock.

Uxn contains both a relative and an absolute variant of the jump instruction. The relative variant is preferred because it uses only three bytes, but it can only be used if the jump target is nearby. The absolute variant uses four bytes, but it can jump to anywhere in memory. Instead of making the programmer decide which variant to use, we can create a JMP macro that assembles to the best jump variant for each situation.

( Basic byte macros. ) %BYTE:n #nnnnnnnn; %16BE:n BYTE:[n 8 <shr>] BYTE:[n 0xFF <and>]; ( Uxn opcodes. ) %LIT:n BYTE:0x80 BYTE:n; %LIT2:n BYTE:0xA0 16BE:n; ( Explicit relative jump. ) %JR:addr LIT:[addr ~here -] BYTE:0x0C &here; ( Explicit absolute jump. ) %JP:addr LIT2:addr BYTE:0x2C; ( Test if min <= n <= max. ) %IN:n:min:max [n min <geq> n max <leq> <and>]; ( Automatically choose the most optimal jump. ) %JMP:addr ?[IN:[addr ~here -]:-128:127 1 =] JR:addr ?[IN:[addr ~here -]:-128:127 0 =] JP:addr &here; ( Perform a jump. ) JMP:end @end

Thanks

Thanks once again to everyone for supporting my work! I love that I have the opportunity to work on all of these different programming systems, and I love that other people are interested in them too.