Properties of operations

Commutative property

A binary operation * on a set S is commutative if:

We say that “x commutes with y“, or that “x and y commute under *“.

Associative property

A binary operation * on a set S is associative if:

Distributive property

A binary operation * on a set S is distributive over a binary operation + on S if:

Fractions

Multiplying fractions

Dividing fractions

Removing common factors

Distributive law with fractions

Adding mixed-denominator fractions

When the denominators have a common factor, first separate these out to the side and then multiply by the uncommon factors. This saves time and effort with complex equations. In the following example, x and 3 are the uncommon factors.

Exponents

Basic forms

Fractional exponents

Negative exponents

Multiplying exponents

Dividing exponents

Exponents of exponents

Distributive law with exponents

Notation for roots

- The expression \sqrt{x} or x^{\frac{1}{2}} represents the positive square root.

- The expression -\sqrt{x} or -(x^{\frac{1}{2}}) represents the negative square root.

- The expression \pm\sqrt{x} or \pm(x^{\frac{1}{2}}) represents both square roots.

- When asked to ‘solve for x when x^2 = 4, both roots are required.

Multiplying conjugate roots

The conjugate of \sqrt{x} + \sqrt{y} is \sqrt{x} - \sqrt{y}, and vice versa.

Rationalising the denominator

For any fraction with a square root in the denominator, we can lift the square root up to the numerator by multiplying both the numerator and the denominator by the conjugate of the denominator.

Equations and inequalities

To preserve an equality, any operation performed on one side of the equality must also be performed on the other side.

Notation

- x \in (a, b) denotes an open interval (where a < x < b)

- x \in [a, b] denotes a closed interval (where a <= x <= b)

- Intervals can also be half-open (as x \in (a, b] or vice versa)

Multiplying or dividing by a negative value

When multiplying or dividing an inequality by a negative number, we must reverse the direction of the inequality (the signs of both values flip and they end up on opposite sides of zero).

We can’t multiply or divide an inequality by an unknown term, because the sign of that term isn’t yet known. To deal with this, we use addition and subtraction to rewrite the inequality to have zero on one side, and then we solve to find the values of the unknown terms.

Critical points

A critical point is the argument of a function where the function derivative is zero (a stationary point) or undefined.

A point at which a term changes sign is also called a critical value.

The critical value of an inequality is, say, for x < \frac{1}{2} the critical value will be \frac{1}{2}, because x = \frac{1}{2}.

Solving quadratic equations by factoring

It is much easier to work with and to solve quadratic equations that are in a factored form. The factored form of a quadratic equation is the product of two linear forms:

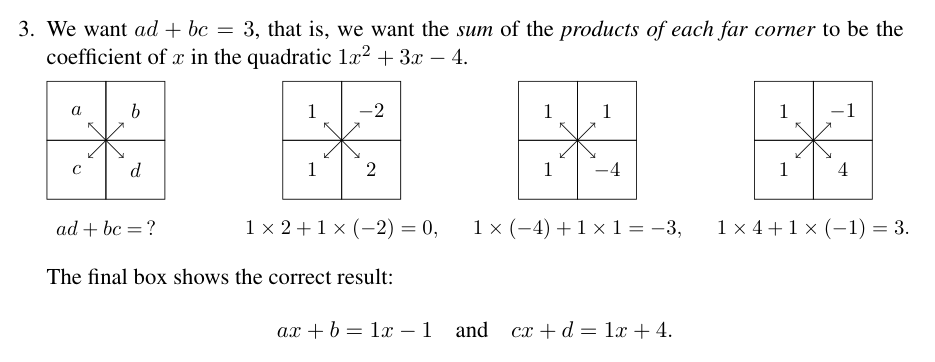

There’s a visual aid with boxes that can help with finding these linear forms from the expanded polynomial form:

When we solve a quadratic equation, we are finding the values for each variable that will make the equation true. Every quadratic equation will have zero, one, or two real solutions.

We can use the fact that if ab = 0 then a = 0 or b = 0 (or both). Given a factored quadratic equation in the form (ax + b)(cx + d) = 0, we know that either ax + b = 0 or cx + d = 0.

In the example equation x^2 + 3x - 4 = (x+1)(x-4) from above, x = -1 or x = 4.

Solving quadratic equations by completing the square

If the result is the difference of two squares (so \frac{b^2}{4} - c \geq 0) then we can solve the equation. If, however, the result is the sum of two squares (so \frac{b^2}{4} - c < 0) then the equation has no real solutions.

Once the equation is in the form (x + \frac{b}{2})^2 - \frac{b^2}{4} + c = 0, we can see that (x + \frac{b}{2})^2 = \frac{b^2}{4} - c. To find the solutions of x, we take the square root of both sides and solve for x:

Solving quadratic equations using the quadratic formula

The coefficients of the polynomial can be substituted into the equation and then solved to directly find the values of x.

The discriminant is the portion b^2 - 4ac beneath the square root, and can be used to determine the number of real solutions. If the discriminant is negative, there are no real solutions to the equation. If it’s zero, there’s one, and if it’s positive, there are two.

Geometry

Equation of a line

A more useful form is y = mx + c, where m is the gradient of the line and c is the y-intercept.

The gradient m of a straight line can be found by choosing any two points (x_1, y_1) and (x_2, y_2) on the line and dividing the vertical displacement by the horizontal displacement:

The gradient m of a line is also given by \tan \theta, where \theta is the angle measured anti-clockwise to the point from the positive x-axis. The angle can be recovered from the gradient with \theta = \tan^{-1} m.

Equation of a line given a point and a gradient

To find the equation of the line passing through (1, 4) with gradient \frac{3}{2}, we substitute the values into the equation m = \frac{y_2 - y_1}{x_2 - x_1}:

Finally, cross-multiply and expand:

Equation of a line given two points

To find the equation of the line passing through two points, we first find the gradient of the line with the equation m = \frac{y_2 - y_1}{x_2 - x_1}, and then we use the previous method with a point and gradient.

Parallel and perpendicular lines

If two lines are parallel, they have the same gradient.

If two lines are perpendicular, the product of the gradients is -1 (that is, m_1 m_2 = -1). This means that m_1 = - \frac{1}{m_2}, so we can find a perpendicular gradient by negating the reciprocal of the original gradient.

Solving linear equations in two variables

For example, to find the value of x and y in the following linear equations:

We start by multiplying every term in one equation by a constant, in order to make the coefficients of one of the terms the same in both equations:

Finally, we can subtract one equation from the other and solve for y, and then substitute that value into one of the equations so that we can solve for x. If there is no valid solution (such as when subtracting one equation from the other would remove both variables), then the lines are parallel.

Equations of the basic graphs

| Equation | Graph name |

|---|---|

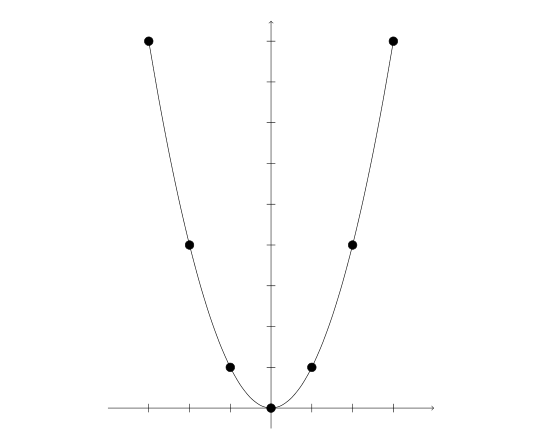

| y = x^2 | Parabola |

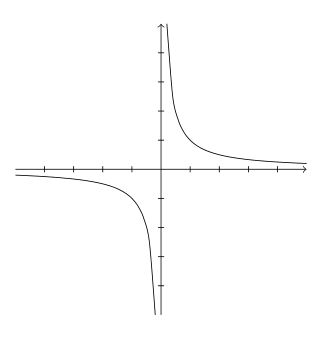

| xy = 1, y = \frac{1}{x} | Rectangular hyperbola |

| y = |x| | Absolute value |

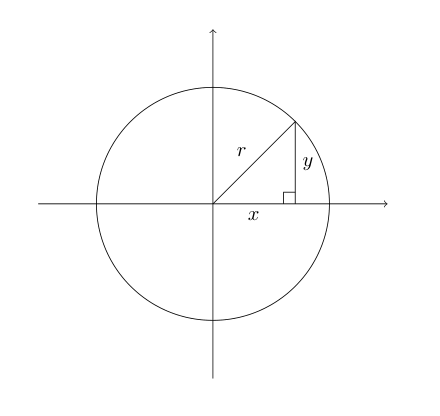

| x^2 + y^2 = r^2 | Circle |

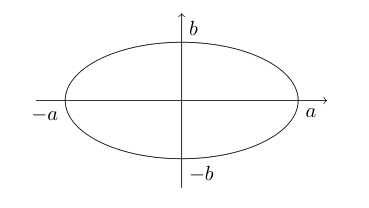

| \frac{x^2}{a^2} + \frac{y^2}{b^2} = 1 | Ellipse |

| \frac{x^2}{a^2} - \frac{y^2}{b^2} = 1 | Hyperbola |

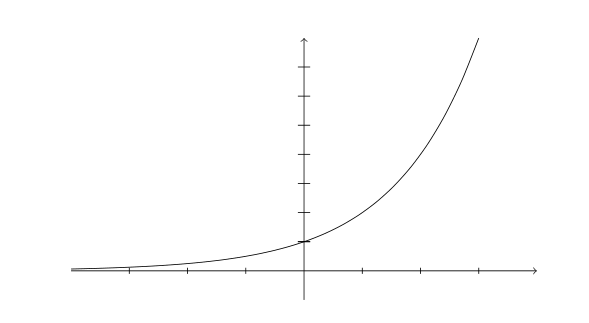

| y = a^x | Power function |

For the rectangular parabola:

- as x \to \pm \infty, y=0

- as x \to 0, y \to \pm \infty

For the ellipse:

- a and b are positive numbers

- -a \le x \le a

- -b \le y \le b

- if y=0, then x = \pm a

- if x=0, then y = \pm b

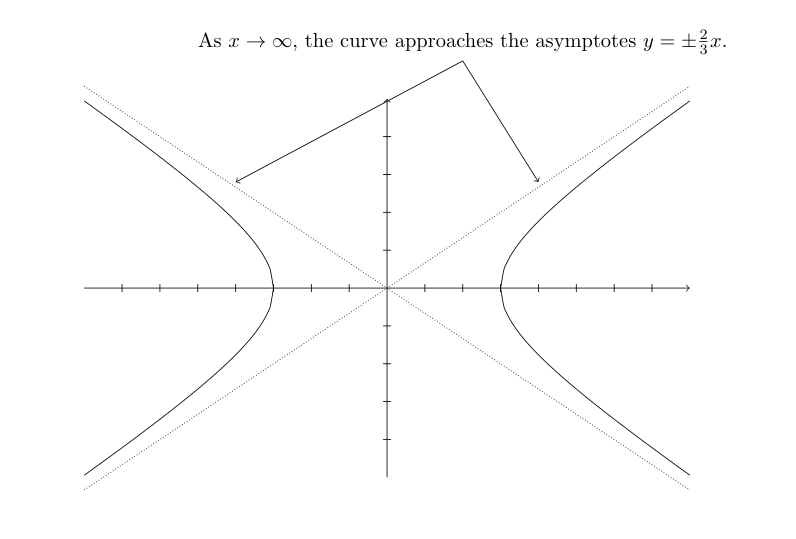

For the hyperbola:

- a and b are positive numbers

- y is undefined when -a < x < a

- if y=0, then x = \pm a

- as x \to \infty, y = \pm \frac{bx}{a}

Asymptotes

An asymptote is a line (not necessarily horizontal or vertical) which a curve approaches as x \to \infty or y \to \infty.